It was fascinating to hear that all 15 of the authorities represented at our recent Personal Travel Planning (PTP) workshop in London were undertaking monitoring, and treating it seriously. Interestingly, there appeared to be less certainty over the reasons for carrying out monitoring and how to make the most of the fact that it had been done!

While it’s great that there is clearly a culture, at least within these authorities, of ensuring they include monitoring within their programmes, this may reflect a degree of uncertainty regarding the DfT’s requirements for Local Sustainable Travel Fund (LSTF) funded projects. It is therefore pleasing to see a Monitoring and Evaluation — LSTF Training Course being organised by Landor Links on behalf of the DfT (and with Steer Davies Gleave as a primary sponsor) that will provide a chance to share more widely experiences of monitoring, and should give extra clarity on the role of monitoring going forward.

Within this context, this article discusses how we might all obtain extra value out of the monitoring work done.

Monitoring methods

It is tempting to digress at this point to a discussion on how monitoring should be done. It is true that one issue which makes drawing lessons more complicated is that there is a lack of consistency in methods used, and probably also to a lesser extent in the KPIs used. However, while the approach adopted for major highway schemes (POPE) is attractive, such a formulaic approach is unrealistic when the nature of the interventions varies so much. A more pragmatic alternative is to focus on answering the simple question: has the intervention achieved its objective of reducing car travel? This pre-supposes that car trip reduction is the common theme, but I think this is reasonable, bearing in mind that to take out any general lessons there has to be some point of commonality.

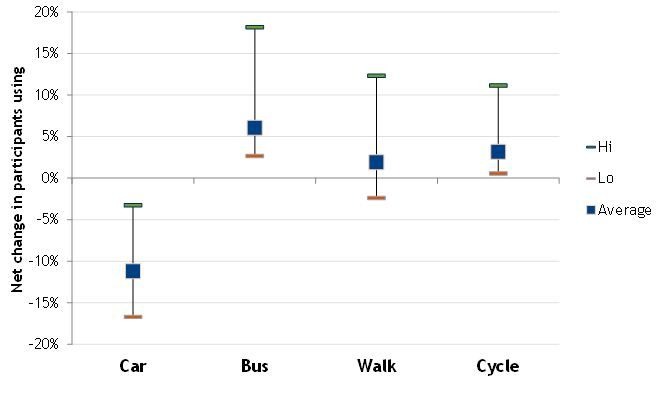

As a case in point, we have, broadly, used two methods for measuring the impact of PTP projects: “before and after” travel diaries; and “after” stated behaviour change questions. To try and learn common lessons across all these projects, we have focussed the analysis on identifying participants who had reduced their car use (as well as those increasing their use of sustainable modes), irrespective of how this change in behaviour has been determined.

As an aside, we did use both these monitoring methods for some projects enabling us to compare the results and explore the impact of the method itself: this is the subject for a different paper and is likely to be covered in our presentation at the forthcoming DfT workshop.

Utilising monitoring results

First and foremost the monitoring outputs can provide re-assurance that the LSTF money has been well spent: this is a valuable message to spread across multiple audiences, both local and national. This helps to demonstrate that the authority can be trusted to deliver, and therefore worth investing in further.

One question that has been raised though is whether the outputs are in the right language, given the current emphasis on supporting the economy. To address this we have developed a spreadsheet based tool (the PTP wider impacts calculator) which converts the transport outcomes typically reported for PTP and behaviour change projects to wider economic impacts and a Benefit Cost Ratio, using available local-area data.

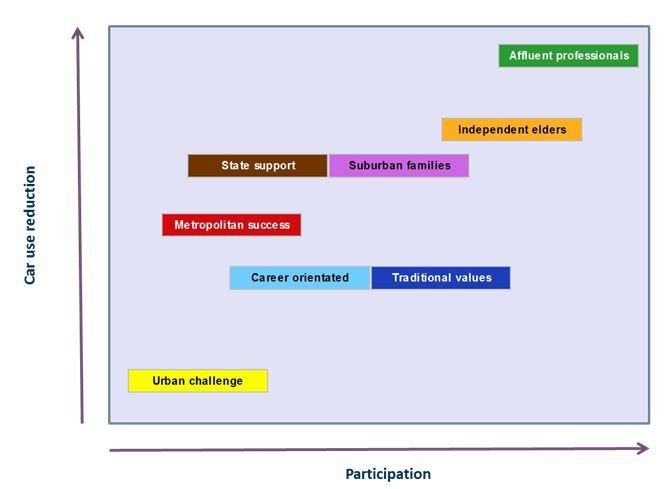

One of the interesting points from our examination of the monitoring results was what this revealed in terms of the factors contributing to success, and conversely, those limiting the impact – some of these were covered in the previous paper in this series, but there’s more that could be done! For example, we have started to look at whether the new accessibility software, TRACC, can reliably tell us how good the local bus services are. If it can, this could be extremely useful in finding locations where the services are good but under-used and hence fertile ground for PTP activity (for cycling we have developed our own tool, the Cycling Potential Index, to do the equivalent thing. Walking potential is another matter though). I was pleased to see that, in general, our Smarter TravelStyle tool proved to be a fair indicator of PTP potential in terms of the characteristics of local people. Having said that, some exceptions were identified and we are now using these to further improve the predictive ability of the tool.

Figure 1: the variability in results between locations has enabled us to explore the reasons for difference and the key success factors

Figure 2: our Smarter TravelStyle segmentation and targeting tool helps us to predict PTP participation rates and levels of behaviour change, such as car use reduction

Compiling the evidence

The general consensus from our workshop attendees was that there was worthwhile value in collating the evidence from LSTF funded projects to build a compelling case that the relatively small behaviour change interventions typically employed. Also, this evidence-based case can then be used to complement larger infrastructure based projects. This is something Steer Davies Gleave fully acknowledges and will now look forward to playing its part in making this happen.

Other articles in this series are available.