This week, Labour Transport Secretary Louise Haigh promised "unprecedented levels of funding" in cycling and walking to boost active travel in the UK.

It is a topic that was featured in our recent Election Reflections event on Transport Policy, at which Steer director Lisa Martin discussed the need to reduce the miles travelled by car in the nation as a whole.

While discussing ‘carrots’ and ‘sticks’ that could impact our convenience and car-centric culture, guest speaker Tom Cohen, Reader of transport policy at the University of Westminster, detailed how improving active travel infrastructure is a quick and cost-efficient win when it comes to changing behaviour.

This year, I relocated to Manchester from London. The city is investing heavily in infrastructure to make walking, wheeling and cycling the natural first choice of transit, but there is a long way to go. Walking around the city can be a huge challenge (especially when pushing the pram with my infant son) with hazards such as pavement parking, badly maintained footpaths and poor drainage in a city of seemingly endless rain.

Cycling can likewise be difficult. Residential streets are commonly used as rat runs, drivers park in cycle lanes and facilities for bike parking can be difficult to locate.

These issues are not unique to Manchester and are ubiquitous in the UK’s metropolitan areas. Walking and cycling have long been overlooked as transport modes. How can we address this?

The still-fledgling UK Government campaigned on a platform of change and is committed to legally binding decarbonisation targets. Louise Haigh MP, the new Transport Secretary, set out her ambition to 'move fast and fix things'. With big promises of bus franchising and rail renationalisation, I can’t help but think about how we could apply this approach to active travel to fix these fundamental problems.

Every bus or rail journey starts and ends with a walking, wheeling or cycling trip of some description. Looking around my local area, it's clear to me that there are many walking and cycling improvements that could be delivered quickly, at a relatively low cost, and are generally uncontroversial.

1. Improve footways, improve accessibility

As a new pram user, I've quickly learned that dropped kerbs are my best friend. For people such as wheelchair users, they are an essential bit of infrastructure that makes the difference between being able to access a street or not. Likewise, tactile paving is equally as essential for people with visual impairments.

These vital accessibility facilities are all too often poorly maintained or incorrectly implemented; auditing the highway network to identify deficiencies with existing infrastructure and pinpointing where lack of provision needs to be addressed would be a good start. A further solution would be to find revenue funding by packaging these minor improvements into larger programmes or adding them to parallel schemes to position them for capital funding.

2. Enact the findings of the Pavement Parking Consultation by banning pavement parking

In 2020, the Johnson government consulted the public on managing pavement parking, but despite 15,000 responses, we're still awaiting an update on the findings. Parking on the pavement is not only anti-social and an inconvenience to people walking but also a serious hazard that forces people to walk out onto carriageways. The sooner this issue is tackled, the better.

3. Give pedestrians priority at key junctions

The lack of pedestrian signals at junctions is emblematic of where transport policy has gone wrong. The endless push for highway capacity and fear of driver delay has created a situation where junctions in heavily populated areas lack pedestrian phases on some arms and inadequate crossing time at pelican crossings. Adding pedestrian signals to all arms of junctions, extending green times so people can cross in comfort, and reducing wait times wherever possible would go some way to rebalancing our motor-centric system.

4. Boost public cycle parking and introduce residential cycle parking programmes

At present, it's typically easier for most people to park a car than it is a bike, and that needs to change. How can we expect people to start cycling when homes, shops and town centres lack dedicated cycle parking?

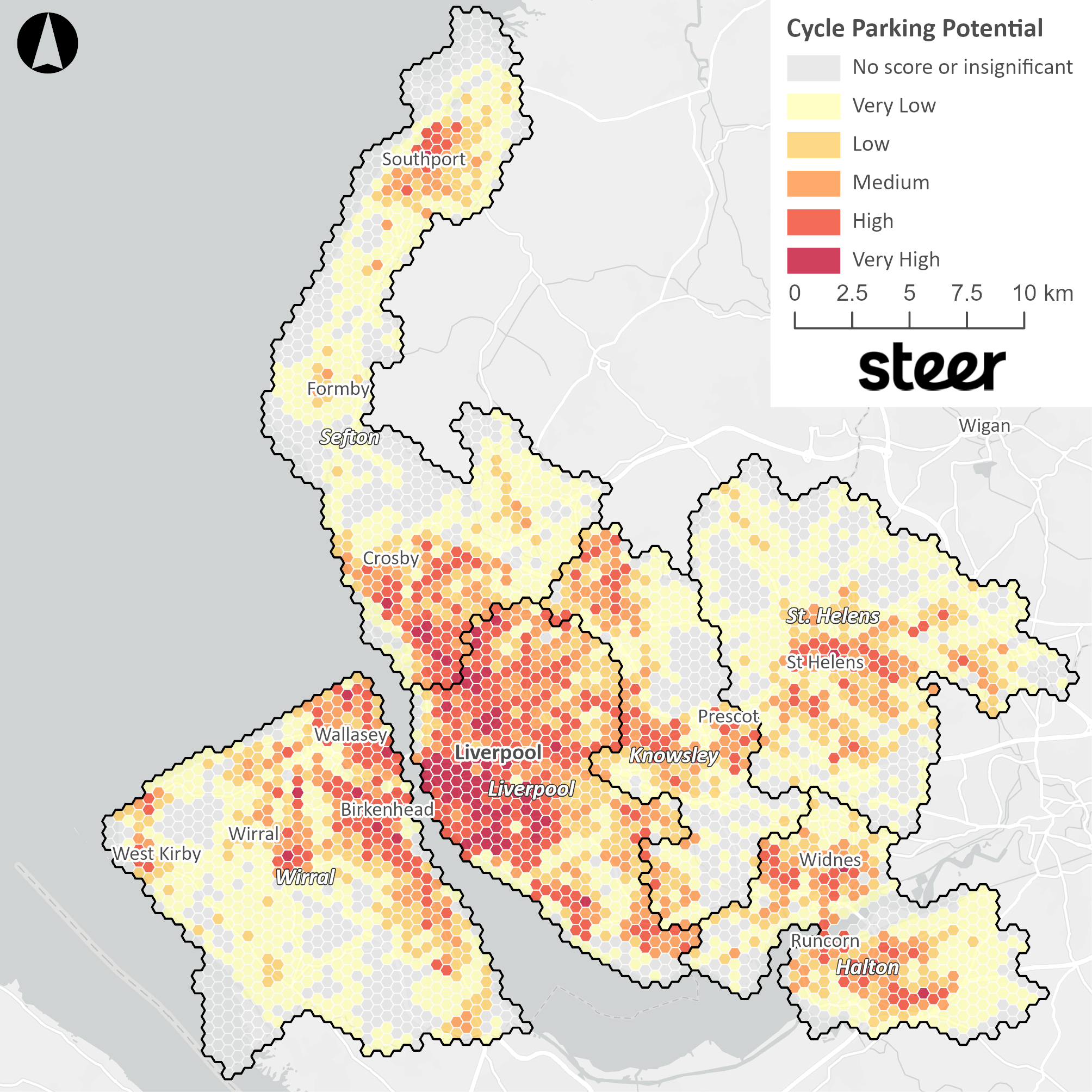

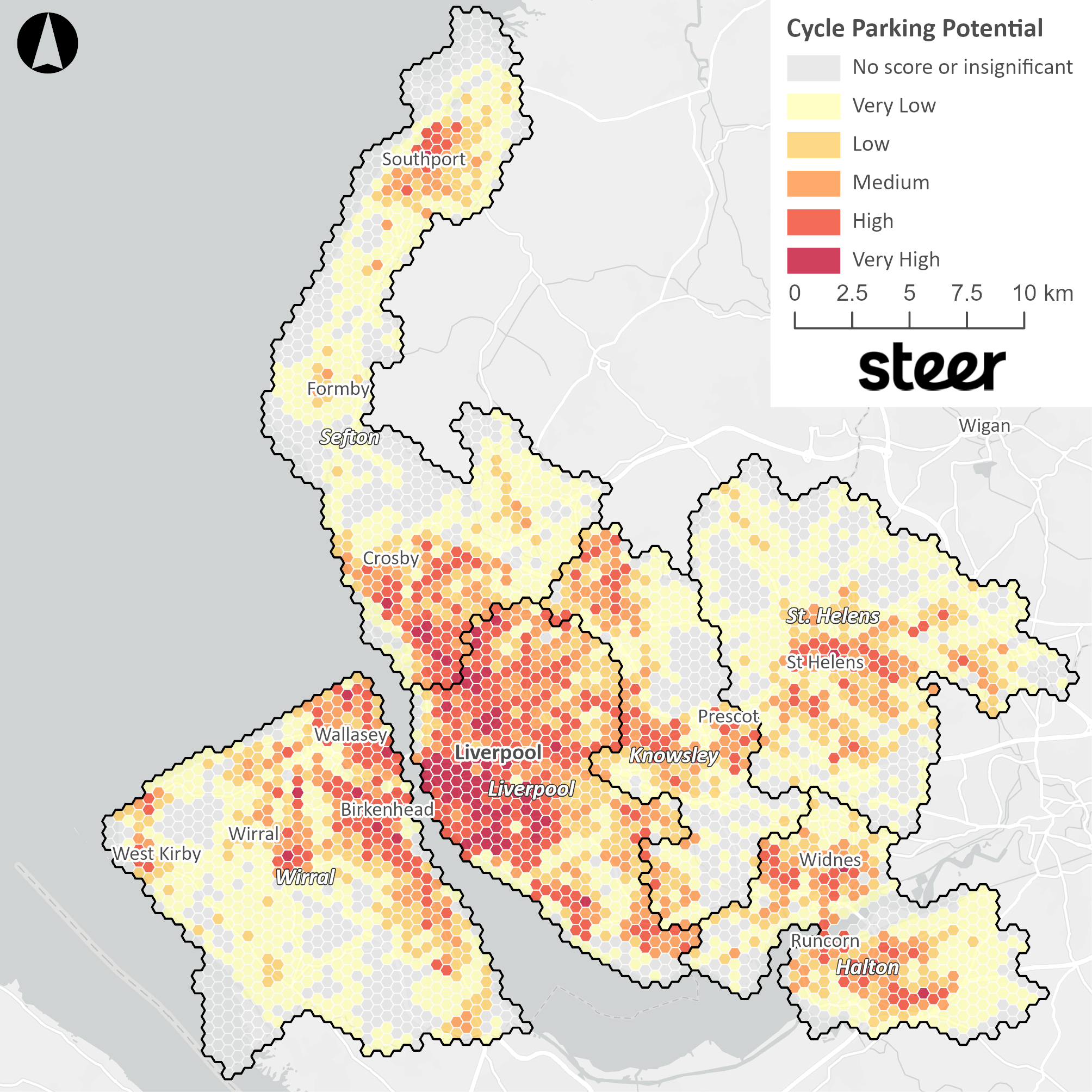

Introducing residential cycle parking programmes and auditing the short-stay provision for gaps and capacity constraints can help remedy this issue. We can start by understanding the likely demand in our areas, analysing key factors such as where housing stock may present issues (e.g. terracing and high concentrations of flats) and where the potential for cycling is highest. From there, we can map the findings and start to develop a method of prioritisation and testing the means and methods of delivery, as Steer did in 2022 - 23 for the Liverpool City Region.

5. Dealing with localised flooding and standing water

Every time it rains heavily, the same places flood near my home, and water can't run away due to inadequate drainage. Depaving (replacing tarmac with grass or planting) and implementing green space and sustainable drainage systems (SuDs) to better manage occasional heavy downpours will not only make life more convenient for those of us in the damp North West but build resilience to the increased surface water flooding that climate change will bring in the coming decades.

Improving walking and cycling infrastructure in our towns and cities doesn’t have to be complex or costly. By implementing these five straightforward interventions, we can create safer, more enjoyable, and healthier environments for everyone. If you’d like to learn more about how to make this a reality in your area, please feel free to get in touch today. I’d love to discuss your ideas and explore potential solutions.