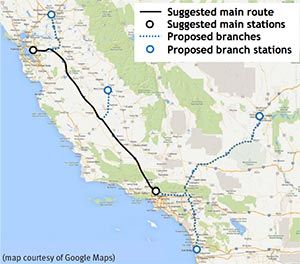

In August 2013, the entrepreneur Elon Musk proposed a novel transport system called Hyperloop to transport passengers and possibly vehicles the 354 miles between Los Angeles and San Francisco in only 35 minutes.

The system is envisaged as a near-vacuum tube containing pressurized pods moving at up to 760 mph and floating on air bearing skis. The idea has generated much publicity, and challenged conventional wisdom on high-speed transport, but will it work or is the founder of the SpaceX program simply shooting for the stars?

Steer Davies Gleave has a long and accomplished record of evaluating the engineering feasibility and providing technical due diligence on new transport projects. While we typically help clients with projects employing conventional technologies including high-speed rail (HSR), Hyperloop presents a technological leap that introduces some new challenges for transport engineers.

The fundamental differences between Hyperloop and its nearest cousin, high speed rail, are:

- the number of passengers per vehicle (pod vs. train)

- the creation of a modified atmospheric environment and

- the removal of the wheel-rail interface.

Capacity and Cost

Speed, or more specifically travel time, is a key factor in travel mode choices and hence competitiveness. Hyperloop’s 35 minutes compares with existing travel times of approximately 1½ hours by plane or 5½ hours by car. But system capacity is also a critical consideration. At a proposed 840 passengers per hour, Hyperloop would offer capacity equivalent to only one or two high speed trains per hour. Overall system costs must therefore be kept proportionally lower than its high speed rail competitor to be affordable and attractive. While we note that the estimated Hyperloop project costs are low relative to HSR, our initial assessment suggests that these estimates may be somewhat optimistic.

A Modified Environment

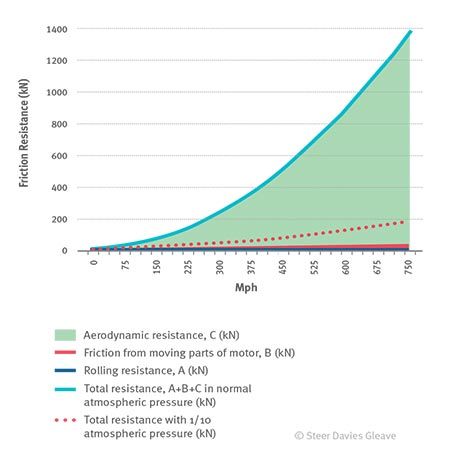

One of the main problems with increasing speed on existing rail systems is that aerodynamic resistance is generally considered to be proportional to the square of the speed (see graph) while the traction power required increases with the cube of the speed. Some suggest that in practice this is not quite the case, but there is nevertheless a rapidly increasing energy price to be paid by going faster through air and it is this that tends to create a practical limit to the normal operating speed of trains.

So higher speeds are possible but rapidly become very costly. The Hyperloop proposal is to create a special environment (the tube) where the air pressure is artificially lowered to 1/1000 normal air pressure. This is about 250 times greater than the differential air pressure in a commercial aircraft at altitude, so Hyperloop doors and their seals will need to be extremely robust to prevent catastrophic depressurization of a pod.

The unique environment creates new safety challenges such as evacuation from the pods in an emergency. Although the Hyperloop report suggests that pods would normally complete their journey in emergencies, the system would almost certainly need to be designed to handle situations where this is not possible. With a close fitting tube, the ‘gull wing’ door designs shown in the report’s illustrations would make it difficult to exit within the tube. One option could be to have internally sliding ‘plug doors’, or end doors, and frequent emergency escape hatches to a continuous walkway along the outside of the tube.

Air Skis

Maglev systems, now operating at over 300 miles per hour, use complex electronic stability systems to maintain a stable gap between track and train. Hyperloop would operate at just over 750 miles per hour, more than twice as fast, with an air cushion of only 0.02-0.05 inches between the wall of the tube and special skis, which it is claimed can work at speeds of up to Mach 1.1 with very low friction. This would, however, require smooth joints, extremely accurate alignment of the tube over long distances, with compensation for the sag of the tubes under self-weight, and very gentle transitions into and out of curves.

To avoid scraping the sides of the tube at near-supersonic speeds, the air cushion would need to be inherently stable and yet react rapidly enough to maintain the same narrow gap under any conditions, even if all power failed or under emergency braking. The differential expansion and contraction of the tubes and supporting towers as a result of the movement of sun and shade on the structure over the day would further complicate the job of maintaining these tolerances throughout the operational day.

Could it Work?

There are many other issues to overcome, as would be the case with any new technology. The Hyperloop idea highlights the residual problems associated with increasing speed using conventional rail technology, but perhaps a hybrid solution borrowing from a range of ideas might provide a step forward but be more achievable in the near term.

Reducing the aerodynamic resistance would be the quickest way to add value, and even a reduction in air pressure to only 1/10 of atmospheric pressure would provide benefits through a significant reduction in comparative friction resistance (see graph). At very high speeds, providing energy to the vehicle can be a problem as traditional overhead electric contact wires get worn very quickly. This would suggest a battery-based or contactless solution such as maglev. Even at a lower average operating speed of say, 300 mph, an enclosed, low pressure atmosphere Maglev system would still be highly competitive in terms of travel time (Los Angeles to San Francisco in around 75 minutes) with lower energy costs than existing maglev systems. It would also facilitate longer trains carrying 3-6 times more passengers per hour than the Hyperloop pods.

Musk offers us an exciting vision of what the transport of the future might look like, but today’s highway, railroad and aviation systems have evolved over many decades and it is likely that advances towards his proposals will be in steps rather than leaps. History suggests that to provide the assured level of reliability and safety that we have come to expect from our transportation systems, such a revolutionary new technology is likely to be many years way. It is unlikely that we will be abandoning our highways, railroads and airports anytime soon, but Hyperloop may serve to inspire the next generation of transport planners and engineers to turn their minds to revolutionary new modes of travel.

Musk may not reach the stars with this ambitious idea, but if he reaches the Moon that will be a feat in itself. We will continue to watch the development of this project with interest.

Friction resistance vs speed

Suggested Hyperloop route map