Rail could be one of the most dynamic and technologically forward-looking industries in the UK, yet passengers are struggling to reap the benefits which innovation could unlock. This isn’t for any lack of inventiveness or ingenuity – the UK rail industry has more than enough of both – but more a lack of co-ordination, effective development and delivery processes, and the sheer number of different agencies involved each effectively throwing up barriers to entry, stopping innovation from getting in. It is sadly ironic for an industry that once represented the pinnacle of British modernity and technological advance. This must change the industry is to meet the expectations of our customers and stakeholders.

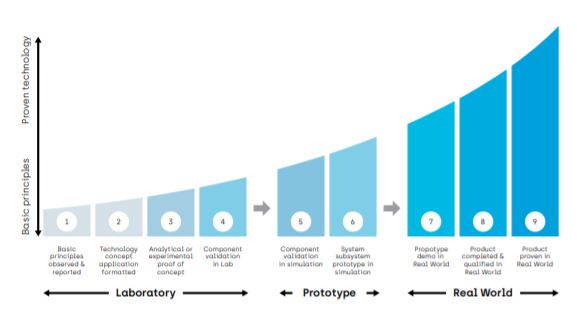

All too often brilliant ideas wither because our industry processes are simply hostile to innovation or too impenetrable to navigate. A good example of this is when innovative ideas or products develop from prototype to real working applications. This is typically the move from Step 6 to Step 7 in Rail Industry Readiness Levels (see diagram below) and is referred to within the industry as the “second valley of death.” The first valley being the transition from lab testing to prototyping.

For many innovation developers (suppliers) and companies (purchasers), this valley is proving to be an unbridgeable chasm. New approaches, if they are truly new, mean risk in some way. This might be risk of failure, a commercial risk (long-term costs or true benefits may not be clearly understood), or a programme risk (a lack of understanding about how long the testing and development may take and when a product could be “in service”). To develop an innovation, potential purchasers need to step forward and collaborate with innovators by providing access to customers, infrastructure or services. For these potential purchasers there is the risk (real or perceived) that the innovation may not deliver the expected outcomes and internal processes (such as investment approval) require a level of certainty which is inherently hard for innovators to provide.

On top of that, the UK has a hugely complex and fragmented industry structure, so for some types of change, such as modification of rolling stock or changes to retailing, a large number of agencies need to be involved and supportive of a change. Aligning the needs of stakeholders with potentially competing or conflicting concerns and technical demands can be daunting. Other industries are arguably less challenging, and provide quicker and less risky commercial returns, for entrepreneurs and SMEs.

Some businesses, such as freight and open access operators, have generally longer time frames to develop and deliver innovative change. Franchises are, by their short-term nature, more challenging, driving a cycle of change delivery at the start of the period where operators must deliver returns in the short-term. The way that franchises are specified, and bids are assessed, can also limit the types of innovation that can be taken forward. A concept needs to have a level of certainty in its deliverability, which can be difficult for innovators and bidders to provide, resulting in these ideas rarely making it to the delivery stage.

Government has attempted to address these challenges with innovation funding and specification of innovation in franchise terms, generating development of great ideas at the start of the innovation process (RIRL 1-5), but very few have bridged the “second valley of death”. The industry is trying to deliver change, and is not short of good ideas, so how can we distill the best ones and get them into the industry at a scale to make a change for the passenger? As I see it there are two fundamental areas we need to address. Firstly, how businesses and their incentives find a line of sight from innovation to the customers and, secondly, how we plan and deliver innovation, breaking it down into a road map of simple steps.

I have recently been fascinated by attempts to introduce new fuel sources to rail to reduce the carbon footprint and cost of operation. Modification of existing vehicles to burn CNG or hydrogen is proven in the UK bus industry and in rail outside the UK – so it should be a fairly simple step to apply this technology to the UK. The Department for Transport (DfT) is providing a stimulus though the requirement to trial emerging novel propulsion or onboard emerging storage in the new East Midlands franchise and there are incubator trials funded by industry innovation funding, which are ready to be scaled up. Any change to a train requires alignment and agreement by, at the very least, operators, fleet owners and infrastructure owner (Network Rail) as well as compliant and potential modification to relevant standards to achieve these changes. DfT and the customer must also be engaged and supportive of the change. Grand Central is very close to delivering a CNG trial on one engine and there are efforts to develop hydrogen and other approaches. It is very likely that not all of these technologies will be practical or scalable – but by trialling many we will find an optimal solution. The CNG trial shows the need for an organisation or an individual with the drive to make it happen and a plan to break down the large end goal of reducing the carbon footprint of a legacy DMU to achievable and supportable steps – through first testing one engine and then scaling it up.

Can we deploy the same approach to say a radical re-think of seating design for commuter trains, or integrating parking and ticketing payment into a system-wide pay-asyou-go approach? The technology for these approaches already exists, and has already been prototyped and trialled in local applications, but needs pulling together and linking up into a workable systemised solution to step over the “valley”. Imagine for a moment another industry that would allow transformative technology like this to stop dead. What would the retail sector look like if it was as cautious and risk averse? Companies such as Waitrose and Amazon have defied all expectations by being quick on their feet and constantly investing in promising new practices and technologies without any guarantee of a short-term return on the risk.