Bank station is one of the most complex underground rail interchanges in the world. It was also voted the ‘worst tube station’ by Londoners in a recent poll. Its problems are caused by how it was first built and evolved during the 20th century and the demand it now faces in the 21st. The story of how Bank became the worst station in London begins in the fifth century with the Romans.

Building London’s roads There are three major issues with Bank station: size, complexity and crowding. Bank station is surprisingly large and incredibly complex, however the station was never planned to be a major hub and to work out how the station became so complex we need to look back at its history.

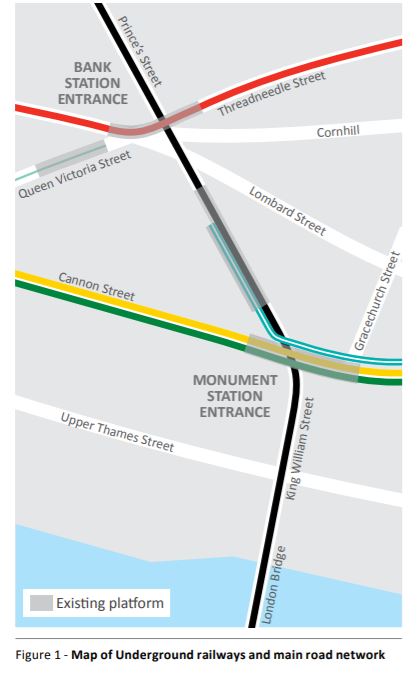

During Roman times, London had a grid of streets which were roughly divided by a stream, the Walbrook, which flowed south into the River Thames. Centuries after the Romans abandoned the city, it was reoccupied and an unplanned network of streets that converged at a bridge over the Walbrook (near modern day Bank junction) took the place of the grid. After the Great Fire of 1666, Sir Christopher Wren proposed a wholly new city plan, with ten streets radiating from a large Royal Exchange Piazza which, if built, would later have formed an obvious and spacious site for a transport hub. Instead, the existing unplanned streets were quickly rebuilt, including five of the eight streets that emanate from Bank junction today. In the early 1800’s, the final two streets were built, King William Street and Queen Victoria Street, to complete the junction as we know it (Figure 1).

This sprawling street pattern has had a significant impact on the area’s transport landscape at the surface but also, unexpectedly, underground.

The road’s influence on the rails

The late 1800’s saw several underground lines built in the area. The first railway, now the District and Circle lines, was built in 1844, just below the surface using ‘cut and cover’ with a station near Monument. Then, in 1898, the first deep level tube, the Waterloo and City line, was built and began operation. To save the cost and complexity of lifts and a ticket hall, its platforms were connected by a 100m long sloping corridor to the ticket hall of the soon to be completed Central line (under Bank junction). Two years later the Northern line was extended from its terminus at Arthur Street with a ticket hall 100 meters southeast of Bank junction at Lombard Street.

These three lines were built in deep level “tube” tunnels and to minimise costly land acquisition, were built directly beneath the streets. The underground railways thereby replicate the unplanned street network above with stations under Queen Victoria Street (Waterloo & City), Bank junction (Central), King William Street (Northern) and Eastcheap (District and Circle), all separated by at least 100 meters as shown in Figure 1. It wasn’t until the 1920s that underground connections between lines were built allowing for sub surface interchanges.

The last major change at Bank was in 1991 when the new terminus for the Docklands Light Railway (DLR) was built below the Northern Line platforms. With the addition of the DLR, the station now has 10 platforms accessed through fifteen entrances and exits, three tickets halls, fifteen escalators six lifts and two moving walkways. Although Bank is a very large station (you can walk over 700m from end to end), it was never designed to be an interchange station, nor was it ever envisioned to accommodate the number of people it currently does.

The problems of the present

The growth of London’s two financial centres (the City and Canary Wharf), linked by the DLR, has made Bank busier than ever, leading to the problems identified in Figure 2.

As the tenth busiest station in London, every weekday 100,000 people swarm the station in the morning and evening rush hours and it becomes overcrowded and even more difficult to navigate.

To manage these crowds, TfL staff are now required to implement safety measures including complex one-way systems, which can require passengers to exit and re-enter the station, and running trains through the station without stopping. While these measures cause significant disruption to passengers at Bank station, the effects ripple out across the network. Passengers that planned to interchange at Bank are forced to adjust their routes which can quickly overwhelm the Underground lines at nearby London Bridge, Liverpool Street and Mooregate stations. Within the station, congestion is particularly bad on the 2.7m wide Northern line platforms which are crowded due to passengers waiting for, boarding and alighting trains. This crowding is made significantly worse as the platforms also function as the fastest interchange route between the Central and Waterloo & City line to the north and the District and Circle lines to the south.

The introduction of the DLR provided an additional north-south interchange route that avoids the narrow Northern line platforms. However, it has created additional stress at Bank station as every trainload of people (over 500 in the peaks) flood into the station. Many of these passengers interchange to the Northern line, and while located directly above the DLR, the interchange requires passengers to follow a circuitous route through the station which causes conflicting passenger flows. Similarly, the Waterloo & City line terminates at Bank and over 400 passengers must either interchange to other lines or make their way to the surface. The route to the surface is via the Central line ticket hall which creates conflicting movements and congestion in the connecting tunnels. A new ticket hall within a major new development at Walbrook will be the first at street level and will provide stepfree access directly to the Waterloo & City line. Although the new ticket hall will bring some reprieve to the north-western edge of the station and within the Central line ticket hall, it is not expected to have a significant impact on crowding in the rest of the station.

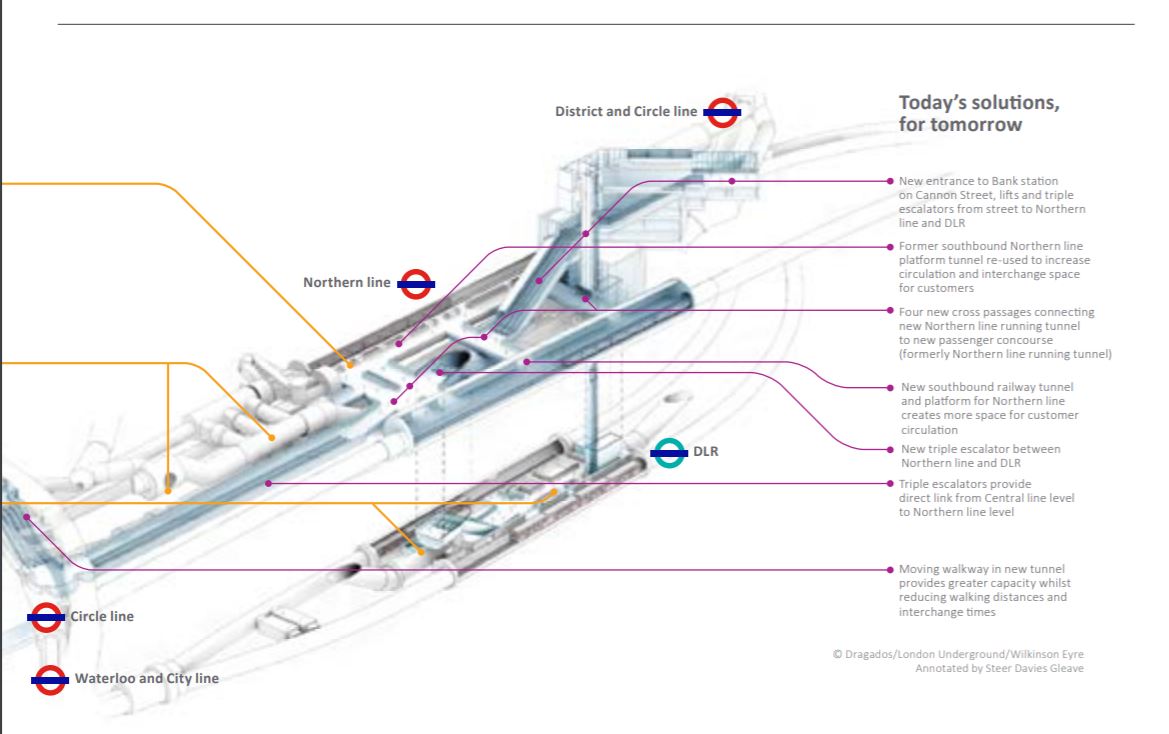

Today’s solution, for tomorrow

With ever increasing patronage, continuing upgrades to the Underground and DLR and many new developments in the City, demand at Bank station is expected to grow significantly. For Bank station and the wider system to not only function, but deliver a high quality service, it is obvious that a major upgrade programme is needed. The Bank Station Capacity Upgrade is TfL’s solution.

The upgrade will help relieve crowding by providing additional circulation space and will facilitate faster and more intuitive interchanges by making routes more direct. This will be achieved by constructing a new southbound running tunnel for the Northern line allowing the existing tunnel to be turned into circulation space. Utilising the old Northern line terminus under Arthur Street, the new tunnel will be bored northwards, narrowly avoiding the Bank of England’s vaults.

A new street level ticket hall on Cannon street will provide both a triple escalator and step-free access to the Northern line and DLR. A new link between the new Northern line concourse area and the Central line will greatly reduce interchange times with the addition of a 95m moving walkway and triple escalator.

This £500 million project is currently progressing through the planning process and the upgrade is scheduled to be opened in 2021. The improvements should relieve Bank station of the overcrowding resulting from its strategic interchange function, simplify its complexity resulting from the post Roman street pattern and lose its title as the ‘worst tube station’ in London.